Kannabiran Memorial Lecture : The Constitution and Scheduled Tribes in Composite State of AP

LIVELAW NEWS NETWORK

3 Jan 2021 12:12 PM IST

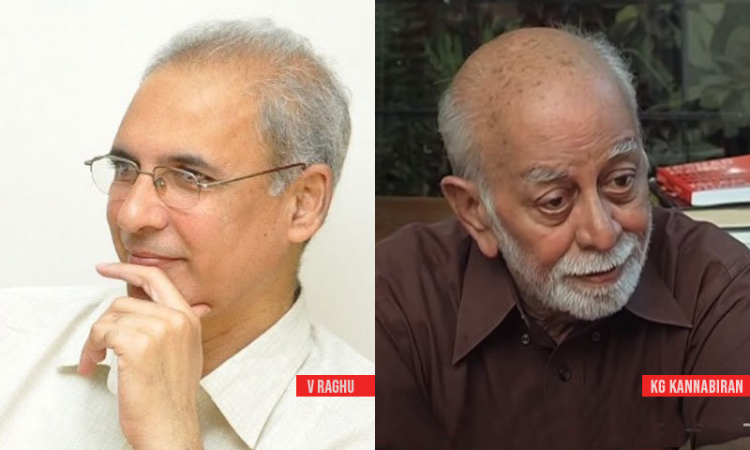

[Abstract: Advocate V. Raghu begins with a reflection on the Arka Vasanth Rao case which led to the enactment of PESA and goes on to speak about cases relating to special protections to Schedule V Areas and reservations for Scheduled tribes in which he appeared with KG Kannabiran. Finally he reflects on a case of negotiating a favourable settlement for workers facing displacement – the last time KG Kannabiran appeared in court in 2009. In all the cases, he points to the ways in which Kannabiran guided the court in its interpretation of constitutional protections].

It is ten years since Sri Kannabiran left us, and yet memories of him are still fresh. In recounting my association with him, I will present a detailed discussion of three cases, of which two cases are concerned with the rights of adivasis/scheduled tribes (autonomy of scheduled areas and classification as Scheduled Tribe)– among his major concerns.

Arka Vasanth Rao case

The first occasion I observed him in the court was when he argued the case of Arka Vasanth Rao vs. Government of AP in 1995 on applicability of the provisions of Andhra Pradesh Panchayat Raj Act to Scheduled Areas. At that time, I did not have any personal acquaintance with him. This writ petition was filed by Arka Vasanth Rao, the Vice-President of the Gondwana Sangarsh Samithi and three other persons belonging to scheduled tribes. The writ petition was founded on the plea that after the enactment of the Constitution (73 Amendment) Act, 1992 by Parliament in exercise of its constituent power, inserting Part-IX comprising Articles 243 and 243-A to 243-O, the legislature of the State of Andhra Pradesh has no power to make a law with respect to Panchayats, extending its operation to scheduled areas in view of the specific constitutional injunction incorporated in Article 243-M. The petitioners contended that due to the large influx of non-tribals into the scheduled areas, the Adivasi population therein has decreased to a considerable extent resulting in the demographic composition of the scheduled areas undergoing a radical change reducing the adivasis to a minority in many parts of the scheduled areas. More than 48 percent of the agricultural land in the scheduled areas went into the hands of non-tribals in spite of legislation forbidding non-tribals from owning lands in the tribal areas.

An area of 30,293 sq. kilometres was populated by 33 scheduled tribes -- 5913 villages spread over 8 districts (Adilabad, Warangal, Khammam, West Godavari, East Godavari, Visakhapatnam, Vizianagaram, Srikakulam and Mahaboobnagar). The total population of the scheduled tribes according to 1991 census was 42 lakhs accounting for 6.3 percent of the total population in the State. The enactment of the Panchayat Raj Act by the State of Andhra Pradesh resulted in reservation for scheduled tribes in scheduled areas undergoing a substantial change to the detriment of tribal interests compared to the earlier position. The exclusive reservation in favour of the scheduled tribes under the V Schedule to the Constitution was now limited only to those cases where the entire territorial constituency lay in the scheduled area and where the population of the scheduled tribes in the constituency was more than 50 percent. This resulted in many elective positions in the scheduled areas going to non-tribals. Out of the 46 Mandal Praja Parishads in the scheduled areas, only 33 were reserved in favour of the scheduled tribes and the remaining 13 were brought into the open pool as the percentage of the tribal population in them was less than 50 percent.

The object of enacting the V Schedule to the Constitution was to preserve and protect the interests of the scheduled tribes in the defined areas, particularly in regard to land to ensure that no erosion takes place in the tribal domain; and in order to achieve this objective, special regulations were enacted under the V Schedule by the Governor, prohibiting the transfer of all land from tribals to non-tribals, regulation of money-lending etc. This objective was watered down by the enactment of the Panchayat Raj Act, which introduced the population norm for the purpose of reservation, which would only lead to the disappearance of the scheduled area itself over a period of time by influx of non-tribals.

The Division Bench comprising of Justice M Rao, and Justice K S Shrivastav referred to the provisions contained in Part IX, Article 244 and Fifth Schedule of the Constitution and held:

"(17)…Practically, the whole gamut of the Panchayat Raj structure is covered by Part-IX. No State law, which is inconsistent with any of the provisions of Part-IX can survive for more than a maximum period of one year. So far as the scheduled areas are concerned, there is a specific injunction by Cl. (1) of Art. 243-M that nothing in Part-IX shall apply to the scheduled areas. It necessarily means that no law concerning the Panchayat Raj institutions as articulated by Part-IX of the Constitution can apply to the scheduled areas. The only exception to this embargo is if Parliament, by law, extends the provisions of Part-IX to the scheduled areas and this is made explicit by sub-clause (b) of Cl. (4) of Art. 243-M.

18. The contention advanced for the State that until Parliament enacts a law under Art. 243-M (4) (b), the State Act must hold the field does not merit acceptance in the face of the clear and unambiguous prohibition contained in Art. 243-N (l) and (4)(b ). This is not a case where the doctrine of occupied field comes into play – that principle applies only when there is a clash between Union legislation and provincial legislation within the area of common path. Abstinence of Union Parliament from legislating under Art. 243-M (4) (b) could not have the effect of transferring to the Andhra Pradesh State Legislature, the legislative power assigned to Union Parliament by Art. 243-M (4) (b). There cannot be anything like inter-delegation of legislative power between Union Parliament and State Legislatures, and no contention, even remotely suggestive of a situation leading to such a consequence can be countenanced."

It is important to note that this successful challenge with regard to the special status of scheduled areas in the matter of local self-government in the AP High Court contributed significantly to enactment of The Provisions of the Panchayats (Extension to the Schedule Areas) Act, 1996 (Central Act No. 40 of 1996) by Parliament the following year in December 1996. Sri. Yerran Naidu, then Minister of Rural Areas and Employment, introducing the bill in Rajya Sabha on 12 December 1996 observed that

"The extension of Part IX of the Constitution by the States of Andhra Pradesh and Bihar to Scheduled areas was challenged in their respective High Courts. The Courts have held the extension of State Panchayat Acts to the Scheduled areas as ultra vires of the Constitution and viewed that Part IX can be extended to the Scheduled Areas only through an Act of Parliament as provided in Article 243 M(4)(b) of the Constitution. This is the reason for introducing the present Amendment which would apply to the Scheduled Areas in eight States" (p. 293)

https://rsdebate.nic.in/bitstream/123456789/144204/1/PD_179_12121996_16_p292_p342_8.pdf

Polavaram Project and the Submergence of Schedule V Areas

Almost a decade thereafter in 2005, several Writ Petitions were filed assailing the action of the then Government of Andhra Pradesh to construct Polavaram project which would result in submergence of more than 250villages in the area covered under V Schedule of the Constitution of India. The Writ Petition filed by me on behalf of Andhra Pradesh Girijana Sangam was one among that batch of writ petitions. When that batch of writ petitions came up for final hearing Senior Counsel Sri K.G.Kannabiran was instructed to appear on behalf of the petitioners.I had an opportunity to assist him in that case. That was the first time I met him in person and the relationship continued till his last breath.

He used to prepare for the case very extensively both on law and facts. Apart from placing the facts and legal aspects effectively, he used to develop a concept blending the facts and law with the idea of justice or legal theory to persuade the Hon'ble Court. I still remember that while making submissions in Polavaram case he placed on record the book Development as Freedom by Amartya Sen, and extracted some passages to explain the theory of sustainable development. In the same case he also placed on record the book Tribal Affairs in India by BD Sharma on V Schedule of the Constitution of India. The contentions raised in that case as extracted by the Hon'ble Court in the Judgment by the Division Bench of the then Chief Justice GS Singhvi and Justice R. Subhash Reddy merit our close consideration:

"Sarvasri K.G. Kannabhiran and D. Prakash Reddy, Senior Advocates, Shri C. Kodandaram, Shri V. Raghu and Shri K.S. Murthy, learned counsel for the petitioners vehemently argued that the decision of the Government of Andhra Pradesh to go ahead with the execution of Polavaram Project should be declared nullity because it has not obtained permission from CWC as per the requirement of Clause VI of the Bachawat Award and approval from the Central Government in terms of Section 2 (ii) of the Conservation Act. Shri Kannabhiran extensively referred to the Bachawat Award and various reports on the construction of dams, River Valley and Hydro-Electric Projects and guidelines issued by CWC and Planning Commission from time to time and argued that the State Government should be restrained from executing the project without obtaining permission from CWC. He submitted that if the project is not cleared by CWC and the State Government undertakes construction of canals, the entire expenditure would go a waste and the people whose land is acquired will be deprived of their livelihood. Shri Kannabhiran submitted that over 7300 acres of forest land is likely to be submerged in the dam and without obtaining prior approval of the Central Government in terms of Section 2 (ii) of the Conservation Act, the State Government cannot undertake construction of the dam. In support of this argument, Shri Kannabhiran relied on the judgment of the Supreme Court in T.N. Godavarman Thirumalpad v. Union of India (2006) 1 SCC 1. Learned counsel for the petitioners emphasized that execution of the project involving utilization of forest land for non-forest purpose and displacement of more than a lakh of people will be an ecological, financial and human disaster and, therefore, the Court must restrain the State Government from executing the Polavaram Project without complying with various statutory provisions. Learned counsel for the petitioners further argued that the environmental clearance granted by the Ministry of the Environment and Forests, Government of India is hedged with several conditions and without fulfilling those conditions, the State should not bepermitted to execute the project.

[…]

The next question which merits consideration is whether the execution of Polavaram Project, which is likely to submerge 276 villages of the Scheduled Areas is liable to be stopped on the ground of violation of Article 338-A (9) read with the provisions contained in the Fifth Schedule of the Constitution.

Learned counsel for the petitioners argued that the construction of dam will necessarily involve acquisition of thousands of acres of land in the Scheduled Areas and this cannot be done in the absence of an order by the President issued under Para 6 of Part 'C' of the Fifth Schedule of the Constitution. Another limb of the same argument is that the construction of dam involves a major policy decision relating to Scheduled Tribes and without consulting the National Commission for Scheduled Tribes as per the requirement of Article 338-A (9) of the Constitution, the State Government cannot execute Polavaram Project. Shri Kannabhiran and Shri M.V. Reddy referred to letters dated 29.10.2005 and 9.11.2005 and argued that the same cannot be construed as consultation within the meaning of Article 338-A (9) of the Constitution. They emphasized that as a result of submergence of 276 villages of the Scheduled Areas, a large number of Scheduled Tribes will get affected and, therefore, the State Government is duty bound to effectively consult the National Commission for Scheduled Tribes. Shri Kannabhiran then referred to Section 52-A of the Government of India Act, 1919, Sections 91 and 92 of the Government of India Act, 1935, the Ganzam and Vizagapatam Act, 1939, the Scheduled Districts Act, 1874, the debates which took place in the Constituent Assembly on 19.8.1949 and 5.9.1949 on the Fifth Schedule and argued that utilization of the land forming part of Scheduled Areas for construction of dam or execution of Polavaram Project should be treated as acquisition of land and this cannot be done except in accordance with Para 6 of Part 'C' of the Fifth Schedule. In support of the argument that consultation should be effective, learned counsel for the petitioners relied on the judgment of the Constitution Bench of the Supreme Court in Union of India v. Sankalchand Himatlal Sheth (1977) 4 SCC 193."

On hearing the arguments of the state and the petitioners, the writ petitions were disposed of in the following terms which have an important bearing for our understanding of the rights of scheduled tribes and special protections to scheduled areas as set out by Sri. Kannabiran:

"1) The construction of Polavaram Project does not per se violate Clause VI of the Bachawat Award, provisions of the Environment (Protection) Act, 1986, Forest (Conservation) Act, 1980, Fifth Schedule of the Constitution and the provisions contained in Section 242-F of the Andhra Pradesh Panchayat Raj Act, 1994. However, the construction of dam would be subject to clearance by CWC and approval of the Central Government in terms of Section 2 (ii) of the 1980 Act.

2) The CWC shall, within a period of three months from the date of receipt of a copy of this order, take final decision in terms of Clause VI (1) of the Bachawat Award. Within this period, the Central Government shall dispose of the application made by the State Government in terms of Section 2 (ii) of the Forest (Conservation) Act, 1980.

3) If the CWC does not approve the project within three months, then the State Government shall be free to avail appropriate legal remedies. Similarly, if the Central Government declines approval in terms of Section 2 (ii) of the 1980 Act, then 7500 acres of forest land shall not be used for implementation of the project. However, the State Government shall be free to avail appropriate legal remedies against the refusal, if any, of the Central Government.

4) The State Government shall not displace the people from 276 villages, which will get submerged in Polavaram Dam and those living in the Scheduled Areas, which are affected by implementation of the project, without giving complete effect to the rehabilitation policy. This would necessarily mean that before the dam is filled and the villages are submerged, the affected persons will have to be rehabilitated, re-settled and compensation paid in accordance with the policy.

5) Wherever the State Government acquires land, it shall take possession only after payment of compensation to the landholder in accordance with Section 17 (3-A) of the Land Acquisition Act, 1894. This would necessarily mean that no person shall be dispossessed from the land without prior payment of compensation in terms of that section."

Scheduled Tribe Status of Lingadhari Koyas

The second case where I had an opportunity to assist him is a Writ Petition filed by Lingadhari Koyas of Adilabad district in 2007 assailing the action of the Government in issuing a memo in respect of their caste certificates. In that case Sri Kannabiran placed on record the book written by Urmila Pingle and Christoph von Furer-Haimendorf, Tribal Cohesion in the Godavari Valley (1998).

In the notification issued under the Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes Order,1950 the 'Lingadhari Koya' community in Andhra Pradesh finds place at Entry 18 in part-I. It was the case of the petitioner that members of the 'Lingadhari Koya' community of Adilabad district, who were issued Scheduled Tribes certificates till 2006, were denied these certificates thereafter by the respondents resulting in a large number of them being unable to secure admission into professional courses and in employment. The petitioner association submitted a representation to the 1st respondent on 14.02.2007 requesting that Scheduled Tribes certificates be issued to members of the 'Lingadhari Koya' community of Adilabad District in accordance with the Presidential Order. The 3rd respondent, by the impugned proceedings dated 19.4.2007 while drawing attention of the4threspondent to the letter dated 20.2.2006, and to the representation of the petitioner dated 14.2.2007, informed him that the department had collected detailed information regarding Lingadhari Koyas residing in Khammam and Warangal Districts and 'Lingadhari' a caste group residing in the district of Adilabad. A copy of the report was enclosed to the said letter and the 4th respondent was requested to take necessary action on the claims of 'Lingadhari Koya' certificates, and the certificates already issued as 'Lingadhari Koya' in Adilabad District, in accordance with the rules framed under Act 16 of 1993.

The petitioner contended that the impugned proceedings was issued without any enquiry being conducted, that there was no caste/group by name 'Lingadhari' and that 'Lingadhari Koyas' residing in Adilabad district could not be deprived of their caste certificates. They submitted that they had earlier filed W.P.No.10557 of 1998 which was disposed of, by order dated 8.7.1998, directing that, as and when applications were received from an individual for grant of Scheduled Tribe Certificate in respect of the 'Lingadhari Koya' community, the same should be considered and disposed of by the authorities concerned in accordance with law. They submitted that, although the A.P. Scheduled Castes, Scheduled Tribes and Backward Classes Issue of Community, Nativity and Date of Birth Rules, 1997 vested power in respondents Nos.5 to 13 to issue caste certificates, they were not exercising the powers conferred on them to issue caste certificates in favour of members of the 'Lingadhari Koya' community of Adilabad District. By way of an illustration they submitted that though Challury Kavari and Santha had applied for being granted the Scheduled Tribe certificate on 23.05.2007 and the Village Revenue Officer of Bheempur, Narnoor Mandal had enquired and had certified that they belonged to the Schedule Tribe of 'Lingadhari Koya', the 4threspondent had refused to receive the applications. And that although applications were submitted by A. Siva Prasad, A. Siva Kumar and A. Srilatha for issuance of Scheduled Tribe certificates enclosing the transfer certificates wherein their caste was shown as 'Lingadhari Koya', their applications were also not received. According to the petitioners there were 125 families, belonging to Lingadhari Koya Community in 9 Mandals of Adilabad district, who were aggrieved by the non-issuance of Scheduled Tribes certificate and, as they had a common grievance, they had invoked the jurisdiction of this Court by way of the present writ petition.

These arguments were extracted in full detail by the Division Bench of Chief Justice Anil R. Dave and Justice Ramesh Ranganathan in the judgment:

"Sri K.G. Kannabiran, Learned Senior Counsel appearing on behalf of the petitioner, would submit…that the 125 families, belonging to the 'Lingadhari Koya' community in Adilabad district, were being extended the benefits of reservation as Schedule Tribes from 1950 till 2006 and that it was only on the basis of the impugned order, and the ethnographic report enclosed thereto, were they denied the benefits of reservation as Scheduled Tribes from the year 2007 onwards….He would submit that Article 342(1) of the Constitution of India conferred power on the President, with respect to any State, to specify, by way of a notification, the Tribes or Tribal communities or part of or groups thereof which would be deemed to be Scheduled Tribes of that caste, that power was conferred only on Parliament, under Article 342(2), to exclude any Tribe or Tribal community or part of or group thereof from the list of Scheduled Tribes notified under Article 342(1), that, under the 1950 Presidential order, Lingadhari Koyas in the entire State of Andhra Pradesh belonged to the Scheduled Tribes and that they were not confined only to the Khammam and Warangal Districts… According to the Learned Senior Counsel there was no ground for denying, the 125 Lingadhari Koya families of Adilabad District, the benefits of reservation and issuance of Scheduled Tribe certificates."

The Writ Petition was allowed holding that since the Parliament alone has been conferred the power to exclude a tribe from the list of Scheduled Tribes in the Presidential Order, "The impugned order, which by way of an executive fiat denies the Lingadhari Koyas of Adilabad District the benefits of reservation, is … arbitrary and illegal." Since Scheduled Tribe status had been conferred from 1950 to 2006 to the Lingadhari Koyas of Adilabad district, "it is also essential that such benefits which …have been extended for more than four decades, is not denied to them on the basis of an ethnographic report prepared behind their back thereby denying them an opportunity of placing evidence, to the contrary, in support of their claim to be Lingadhari Koyas in Adilabad District." As a result the impugned proceedings dated 19.4.2007, which sought to make a distinction between Lingadhari Koyas of Khammam and Warangal Districts and Lingadhari Koyas of Adilabad district was quashed and the authorities were directed to receive applications submitted by members of the Petitioner Association, and others similarly situated, and consider their case for grant of Scheduled Tribes certificates "in accordance with law, without placing reliance on the ethnographic report enclosed to the impugned order, within a period of three months from the date of receipt of the applications."

The Birlagadda Case

The last case Sri. Kannabiran appeared is a case of a slum namely Birlagadda in Kurnool town in 2009. The brief facts of this case are that the land on which these habitations were located belonged to Tungabhadra Industries. Many of these habitants were the workers of Tungabhadra Industries and their dependents. Later the company went in liquidation and the proceedings were initiated by the official liquidator. As a part of those proceedings the liquidator wanted to evict these habitants so that the land can be put to sale to settle dues of banks and other debtors out of the sale proceeds. As there was resistance from the habitants to vacate that place stating that they were landless poor persons and their claims as workers of the company for their dues were pending. The Liquidator moved an application before the Hon'ble court seeking a direction to evict the habitants with the assistance of revenue authorities and police. A survey was conducted by the revenue authorities and report was submitted to the Hon'ble court enumerating all the details of more than 400 habitants. An application was filed by the affected persons to implead them and the same was allowed. As a result all the habitants became parties to the proceedings. Sri KG Kannabiran was instructed to appear on behalf of the habitants. When Kannabiran sir entered the court hall, immediately Justice Nooty Rammohan Rao asked him why he came to court. Kannabiran informed the Hon'ble court about the case in which he was instructed to appear. Hearing this Justice Rao asked why he took all the trouble for that case. "My Lord, I want to have a satisfaction that I have done a good thing before the end of my life," Kannabiran answered.

After hearing and negotiations held between the parties it was decided to resolve the issue amicably by granting certain extent of land owned and belonging to the company under liquidation in favour of the enumerated 418 'encroachers' of Birlagadda lands, most of whom are the former workmen/employees of the company under liquidation or their dependents. By transferring certain portion of the land in their favour on a permanent basis towards full and final settlement of their claim. The proposal was to develop it in to a habitable residential colony, so that each one will secure a plot of a minimum of 48 sq. yards size; have roads of 18' width; and have some other common facilities, which are so essentially needed for a decent standard of living, such as a community hall, school premises and an open space and an area to be set apart for religious activities. The company's land to a certain extent of nearly 4.00 acres were also be retrieved simultaneously, free from encroachment which could then be put to sale by the liquidator to discharge the debts due by the company under liquidation to several of its creditors. It is observed in the order that

"This arrangement has been worked out by this court with a pious hope that the disputes and recurrent troubles between the workmen on one side and the company on the other will be brought to an end forever and there will not be any further scope for litigation in future. It is also intended to ensure that the standards of living of these workmen will get substantially improved with this arrangement."

That was on 1st May 2009. Kannabiran was very jubilant and his face was glittering with contentment. None of us thought that would be the last occasion on which he would appear in court. But to my knowledge he could not appear in court thereafter.

Conclusion

A book often quoted by him is Grammar of Politics by Harold J. Laski (1925) and he used to draw the attention to the chapter on judicial process in that book. Sri Varavara Rao while speaking on the eve of release of Kannabiran's memoirs in Telugu, 24 Gantalu (24 Hours) stated that Kannabiran used tell his juniors that the case files in their hands contain not only papers but also the lives of people. Kannabiran always used deal with each case as if he was dealing with the lives of people involved in that case.

Cases Cited

AP Girijana Sangam vs. Union of India &Ors. WP No. 19067 of 2005 (Polavaram case).

Arka Vasanth Rao And Others vs Govt. Of A.P. And Others, AIR 1995 AP 274 (equivalent citations: 1995 (1) ALT 600 & 1995 (1) ALD 801).

M/s Tungabhadra Industries (In Liqn) Represented by Official Liquidator, High Court of Andhra Pradesh vs. District Collector, Kurnool Dt & Ors. Company Application No. 2331 of 2004 in RCC No 22 of 2000. 1st May 2009.

The District Lingadhari Koya Tribal Association represented by its President, Mr. J Divakar, Utnoor, Adilabad vs. Government of AP & Ors. WP 22511 of 2007. 12 July 2009.

Acknowledgments: I am grateful to Sri. M. A. Gafoor, Ex. MLA, Kurnool for providing copy of the court order in Birlagadda case. I thank Kalpana Kannabiran for her feedback and comments.[V. Raghu has been practicing as an Advocate since 1989 in the High Court of Andhra Pradesh at Hyderabad dealing with civil, criminal and constitutional matters, moving to the High Court of Andhra Pradesh at Amaravathi after state reorganization].

This is the seventh lecture of K G Kannabiran memorial lecture series.

First Lecture by Justice B Sudershan Reddy, former Supreme Court Judge -Death Of Democratic Institutions: The Inevitable Logic of Neo-Liberal Political Economy & Abandonment of Directive Principles of State Policy.

Fifth lecture by Justice K Chandru : Need For More Kannabirans Felt Now With Ever Increasing Human Rights Violations : Justice K Chandru

Sixth lecture by Advocate BB Mohan : Criminal Law and Human Rights: 'Distinctive Discrimination' and Article 21 Rights to Fair Trial